For us to hear a sound, soundwaves go through various media as they travel from the external environment to the brain for processing. Because we have varying levels of sound wave intensity, they must be regulated appropriately.

The middle ear cavity, found within the temporal bone, extends from the tympanic membrane to the outer wall of the inner ear. Within the middle ear cavity lies the ossicles, which are amongst the smallest bones in the human body.

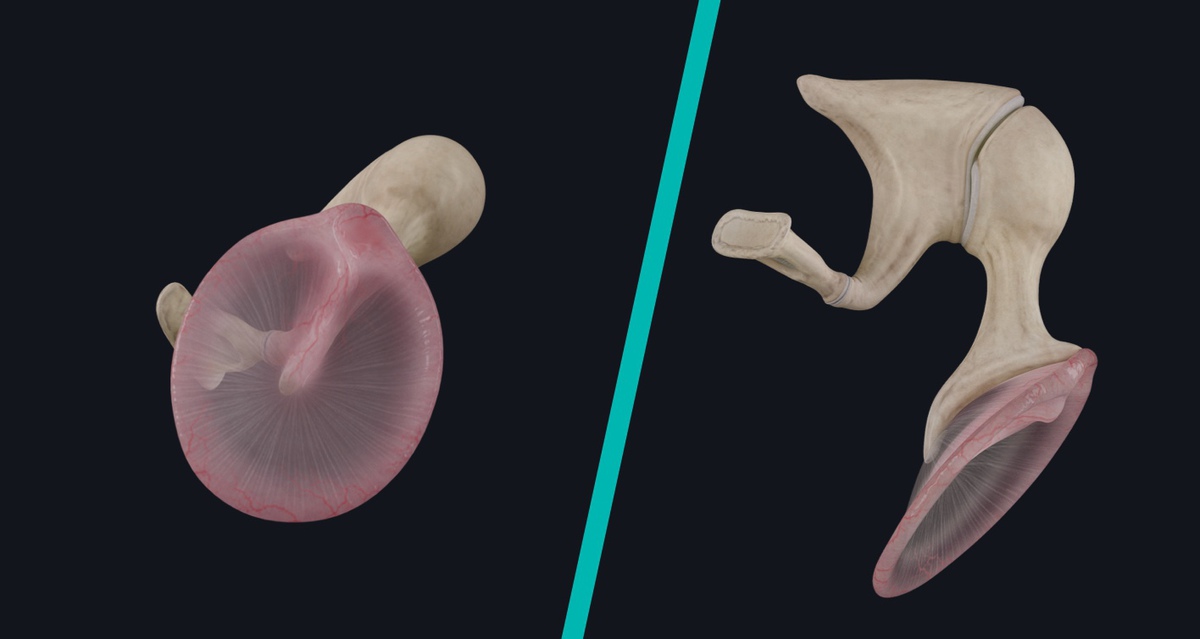

The ossicles are named after their respective shapes:

- Malleus (hammer)

- Incus (anvil)

- Stapes (stirrup)

They articulate with each other via synovial joints, and they form a chain running from the tympanic membrane to the oval window.

Mechanical vibrations produced from sounds travel through the external ear to the tympanic membrane. Excessive vibrations are then tapered down as they are transmitted via the ossicles to the oval window. Here fluids of the inner ear move and excite the hair cells located in the cochlea.

For sound to transmit to the middle ear, the vibrations in the air must be changed to vibrations in the cochlear fluids. Naturally, this is difficult because there is a lot of resistance as sound travels between an air-fluid medium, a phenomenon known as impedance. The tympanic membrane and the ossicles have the critical function of reducing this impedance. Thus, modulating the impact of sound as it travels in the ear.

Because the middle ear cavity is vital for the transduction of sound, damage to any component within the cavity can lead to hearing loss.

Explore the minute anatomy of the ear with the world’s most advanced 3D anatomy Atlas, including a revamped Head & Neck and a detailed model of the Cochlea. Try it for FREE today.